- Home

- Donna Cousins

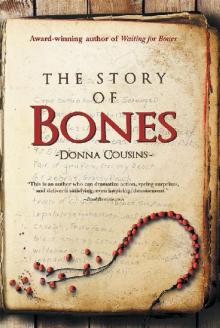

The Story of Bones

The Story of Bones Read online

Praise for Waiting for Bones

“A taut thriller that mixes detailed survivalist fare and character study with aplomb, expertly framed by a vibrant setting.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Cousins begins with a mystery and ends with—I won’t tell! In between, the book is just plain hard to put down.”

—John Lionberger, author of Renewal in the Wilderness

“Four American tourists in the wilds of Africa … learn their limitations and their strengths after their guide vanishes. Every step brings perilous confrontations with fierce animals, malevolent plants, and—most dangerous—their own assumptions.”

—Jane S. Smith, author of The Garden of Invention

“A gifted storyteller whose skills are apparent on every page.”

—Joyce Lain Kennedy, syndicated columnist

“The writing … is considered and memorable.”

—ForeWord Reviews

Praise for Landscape

“The fifty-page climax of the book is one of the most exhilarating stretches of suspense writing I’ve read in ages.”

—John Lehman, BookReview.com

“Absorbing reading. Fast-paced and intense, a fascinating window into the world of medical technology and the environment.”

—Judith Michael, New York Times best-selling author

“If you can put this book down before you find out what happens next, you have a tighter rein on your curiosity than most people.”

—New Mystery Reader

“It’s a choice between family lives and wider community safety that keeps this novel riveting.”

—Midwest Book Review

Novels by Donna Cousins

Landscape

Waiting for Bones

The Story of Bones

THE STORY

OF

BONES

DONNA COUSINS

THE STORY OF BONES

Copyright © 2018 Donna Cousins.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, names, incidents, organizations, and dialogue in this novel are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

iUniverse

1663 Liberty Drive

Bloomington, IN 47403

www.iuniverse.com

1-800-Authors (1-800-288-4677)

Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

Any people depicted in stock imagery provided by Thinkstock are models, and such images are being used for illustrative purposes only.

Certain stock imagery © Thinkstock.

ISBN: 978-1-5320-3544-9 (sc)

ISBN: 978-1-5320-3545-6 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017917092

iUniverse rev. date: 12/21/2017

CONTENTS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Author’s Note

Chapter 1

About the Author

For Harper, Dotch, and Alex

Happiness requires something to do,

someone to love,

and something to hope for.

—African proverb

Until the elephants tell their story,

the tale of the hunt

will always glorify the hunter.

—African proverb

1

I WAS TEN YEARS OLD THE day Skinner taught me that a person could be the most dangerous creature in Africa. It was a valuable lesson for a boy raised with a deep respect for living things. I was learning to coexist with the natural world, yet I remained ignorant of the many ways human beings can inflict misery. Fortunately, I didn’t know that Skinner’s life and mine would become as interlocked and tangled as an old osprey nest. All I hoped for then was to be rid of him.

On that awful day, the cobra that lived in the ditch beside our house decided to coil itself in the grass next to my bicycle. I didn’t see it until I had tied my books onto the rebar welded over the back wheel and undone the chain. By then I was standing in the narrow space between the bike and the splintered boards that held up our front porch. Through the rusted metal frame I saw the pointy reptilian head rise and sway, hood flared to full effect, and I found myself staring into the blunt-eyed gaze of one of the world’s deadliest snakes.

I knew it was “our” cobra because of the mark on its back where my father previously whacked it with a hoe before flinging it off the porch. “A Mozambique spitting cobra,” he had announced, always wanting to teach me something. “Unless it tries to come into the house, we let it be.”

I stood as still as I could. I wasn’t a meal for this animal, and once it decided I posed no threat, it would calm down and slither away. I had learned enough about the creatures that shared our acre of the African bush not to try anything fancy. “Kill a fly, and a thousand come to its funeral,” my father had said. “Wild animals aren’t much interested in people unless we get in their way. Just let them be.”

My father was a decent hunter who helped feed our family by shooting game, usually an impala, bushbuck, or other species of antelope that thrived in the bushveld where we lived. Although he said he liked hunting—the focus it required and the way tracking and aiming heightened every sense—he killed only for the pot, to feed our family. He detested ornamental kills and, worse, the slaughter of animals for ivory or horn. He told me about poachers who massacred with automatic weapons, leaving the landscape strewn with the hacked and bloody corpses of elephants and rhinos. I had never seen such evidence, and I hoped I never would.

So far, snake meat hadn’t turned up on our dinner table, not even during the long, dry season when we ate little but the cassava we grew and whatever game hadn’t migrated to wetter territory. The muscular cobra whipping its tongue in my direction could have fed our whole family. Uncoiled, it was longer than my bicycle. Fat too—good at catching mice and rats, which was why Mama had tolerated it in the yard for so long.

The fixed line of the up-curved mouth formed a frightful smile. My heart was racing, but I stood my ground. I knew cobras had weak vision and struck at movement. If I blinked too much, it could spit in my eyes. I squeezed them closed and stared into blackness. A warbler chirped. A fly whined past. Zola, my older sister, had already left for school, so the usual girlie chatter and thwack-thwack-thwack of flip-flops on the floorboards had ended. I could hear my mother inside trying to soothe the wailing baby. My father—Baba, we called him—was probably still in bed.

With my eyes closed I sensed rather than saw the cobra, not two feet away, holding itself erect,

trying to figure out whether I was there. I had on the gray Fightin’ Irish T-shirt I had found in the trove of used clothing at the Sisters of Charity, so long it almost covered my blue shorts, and the sandals Baba had made from the tread of a tire. I remember how vulnerable I felt, standing there bare skinned and tender. The slightest current of air rifled my body. Goose bumps rose on my arms. Baba had once watched a viper slide across his naked feet while he stood quietly, waiting for it to leave. I tried not to move my toes. The only thing to do was wait, the way Baba had done. Just wait until the cobra settles and decides to go.

Even with my eyes shut tight, I knew Skinner was coming down the road. When Skinner was in a hurry, his gait combined a skip and a sidle, his long body turning left and right as he rabbited along. I was familiar with the sound he made because he passed our house often, looking for my sister Zola. I had seen him turn his oily charm on her and other girls too. He would look them straight in the eye while he lied about having a job or boasted that he had killed a hyrax with his bare hands. He was a shameless girl chaser, as far as I could tell. I was glad Zola avoided him most of the time.

The double crunch, double crunch of his sneakers grinding against the dirt abruptly stopped, and with a stab of fear I realized he was taking in my predicament. When he hollered, “Don’t move! I’ll get him,” fresh dread speared through me. “Getting” a cobra was far more dangerous than simply letting it go its own way.

Skinner wasn’t known for good deeds or sound judgment. He came from a nasty background that had done nothing to improve his character—a brutal, felonious father and a trodden, defeated mother who died of abuse. Already Skinner’s reputation for lying, delinquency, and bullying suggested a familial pattern. I swallowed hard and felt a trickle of sweat course down my back. This could go wrong, very wrong. I wished Skinner would just disappear.

I heard him run onto our porch, stepping lightly now, and down again. I wanted to know what he was up to, so I cracked open my eyelids. Through thickets of lashes I saw him creep forward, toward the snake and me, holding aloft Mama’s round tin washtub. The washtub? I considered making a run for it, but first I would have to sidestep around the bike, a reckless move with a nervous cobra flipping its tongue an arm’s length away. My stomach contracted as I watched Skinner pause to consider the angles and then snatch another look toward the house. I gathered that this was a show he hoped Zola would see.

Wearing a look of utter concentration now, he took aim. The tension in his body resembled the stillness of a wild creature preparing to strike, every nerve and muscle connected directly to his will. We both knew our lives were at stake—mine, in the direct line of fire, for sure. Venom from this snake could cause a person to seize up like a stone, become paralyzed, and suffocate within minutes.

What happened next is a big blur, but it must have gone like this: Skinner threw himself down on the overturned washtub, trapping the cobra, or most of it. The bike knocked into me so hard that I tipped backward against the rough boards and sank to the ground. I was only vaguely aware of the splinters clawing through the back of my T-shirt. All my attention was focused on the mayhem inside the tub, where the enraged snake unleashed a power so mighty that I couldn’t believe it was the work of one small creature. The cobra thrashed and banged, making a horrible racket against the metal and bucking Skinner, who had laid his entire body across the top of the jerking, bouncing platform. He had captured all but about ten centimeters of tail. The protruding length whipped back and forth with terrifying force, kicking up a mess of dust that got in our eyes and noses and made Skinner cough.

Still sprawled on the ground, I sat almost eye level with the slashing, lashing section of manic snake flesh. The edge of the tub hadn’t cut into or even deeply dented the tail, as far as I could tell. The ropey muscle swiped and pounded the earth, whipping up gobs of grass and dirt. I felt sure the snake was capable of beating its way out and attacking both Skinner and me. But with every thrust and buck, the edge of the tub sank further into the cobra’s battered back. I both hoped for and dreaded the moment when living tissue would finally give way to unyielding metal. The maiming of animals went against everything I had taken to heart about life in the African bush. To cut apart a living creature was unthinkable to me. But then, I had never been forced to defend myself against an animal that wanted me dead.

I blinked away the grit in my eyes, scrambled to my feet, and stepped over the bike to fall on top of Skinner. I was a few years younger and many pounds lighter than he, but I guessed our combined weights would be sufficient to inflict a mortal wound. Beneath me, Skinner’s chest pressed down so hard he gasped for air. The load of us suppressed the tub’s herking and jerking but did nothing to reduce the frenetic pounding within. We endured the terrible commotion for what seemed forever. Then, at last, the thumping slowed. Skinner pointed to a thread of fluid winding into the depression formed by the thrashing tail. We watched the dark, wet pool enlarge as though our lives depended on it, which they did. The noise gradually diminished to a listless, hollowed rap, then stopped.

Skinner listened for a minute or two. “It’s dead. Get off me.”

He tried to throw me over, but I kept my arms tight around him with my hands gripping the sides of the tub. “How can you be sure?” My voice against the back of his head sounded small and weak. I knew the cobra could still be alive, lying in wait for a glimpse of daylight and the chance to nose out and sink its fangs in the nearest available flesh. “It might be faking.”

“When it looks dead, sounds dead, and feels dead—it’s dead. Now let me up, dung beetle. I have places to go.”

I doubted that. Skinner had quit school years earlier to spend his days getting into trouble with a rough bunch of teenagers who swore, stole, and terrorized the smaller kids. Skinner wasn’t one to keep appointments or, I was about to learn, finish what he had started.

He wriggled out from under me, cursing. When he had freed himself, he stood and brushed the dust from his shirt, eyeing the porch, still hoping to see my sister. I rolled over, taking care to keep my weight centered on the tub, and sat up, cross-legged, gripping my knees. A faint thump sounded below.

“Where’s your uniform, Fightin’ Irish?” he sneered, looking at my T-shirt.

“In the wash,” I lied.

He eyed the washtub under me and snickered. “I hope not.”

Our school principal, Mr. Kitwick, encouraged uniformity in students’ clothing—blue and gray, at least. He was a tall, bony man who reminded me of a stick insect, an effect heightened by the long, sharp creases in his trousers. The gray suit he wore every day was shiny from pressing, and the knot in his blue necktie pressed against a mighty Adam’s apple. Beneath the buttoned-up exterior, though, Mr. Kitwick was a practical man who understood the realities of his threadbare district. He usually looked the other way when our school clothes strayed from the standard uniform, and he was quick to make exceptions for financial hardship.

The burden of poverty was something I had learned to endure and even overcome from time to time by wearing to school a particularly choice, preworn T-shirt. I prized the swagger in my Fightin’ Irish tee, although the words were risky around kids who actually liked to fight. The problem of dressing appropriately for school was even harder for my sister Zola. Her ill-fitting skirts and tops compounded the embarrassment of a budding body that drew unwanted attention from the boys. She had started cutting class days in a row, a secret she had sworn me to keep.

Now, leaning over me as I sat on the washtub, Skinner waggled a finger in my face. “You owe me, you little runt. I saved your life. Be sure to tell Zola.”

“You did not. That snake would have gone away if you hadn’t trapped it. You made it angry, and it’s still alive.” My voice rose in pitch. Under me I felt the presence of the living, breathing reptile as surely as I felt my own pulse.

Skinner stared at me as if measuring the exact depth of my stupidity. “

That snake is as dead as dead can be. You’re lucky I’m letting you keep it. The skin will make a nice belt.” He turned toward the road. “Be sure to tell Zola.”

“It’s still alive!” I shouted at his receding backside, feeling tears leak from my eyes. The vibrations in the metal had started up again, urgent and threatening. I was terrified and, at the same time, heartsick that we had treated the cobra so brutishly and wanted it to die. I felt ashamed to be sitting on Mama’s slimed and bent washtub, not knowing what to do. I despised hearing my sister’s name on those sneering lips. I didn’t like missing school. And most of all, I hated Skinner.

I didn’t move from my seat on the washtub, and I didn’t call for help. In minutes Skinner had turned an almost normal school day into unthinkable torment. The rapid turn of events had left me hollowed out and dazed. I sat stiff-backed, frozen with fear of the creature trapped under me. Inside the house the baby had stopped crying, but I was too embarrassed by my predicament to summon Mama and too hungry for Baba’s approval to admit I couldn’t fix this myself.

My father encouraged self-sufficiency, an expedient attitude for a man with three children, an overburdened wife, and a weakness for drink. In spite of Baba’s late, boozy nights and long, quiet mornings, he was a hero to me. I thought he knew everything worth knowing, and I never doubted he loved us. I had come to see his intemperance as a cruel foe that came knocking unbidden, like a recurring case of malaria. He would awaken soon, take a long drink from the pump, and without saying a word to anyone, lift a rake or watering can and retreat as if to do penance among the jagged rows of corn, potatoes, and cassava he managed to keep alive most of the time. I recoiled at the thought of him finding me helpless, sitting like an imbecile on Mama’s overturned washtub.

The Story of Bones

The Story of Bones